優秀範文的閱讀與學習是掌握寫作技巧的最快方式之一。一篇優秀的文章在主題設置,文章框架,行文方法以及敘事手法上都擁有其突出的地方,值得我們藉鑑。

同時,在同學們參與寫作競賽時,閱讀這項比賽的獲獎優秀範文將幫助同學們理解比賽要求以及評委偏好。

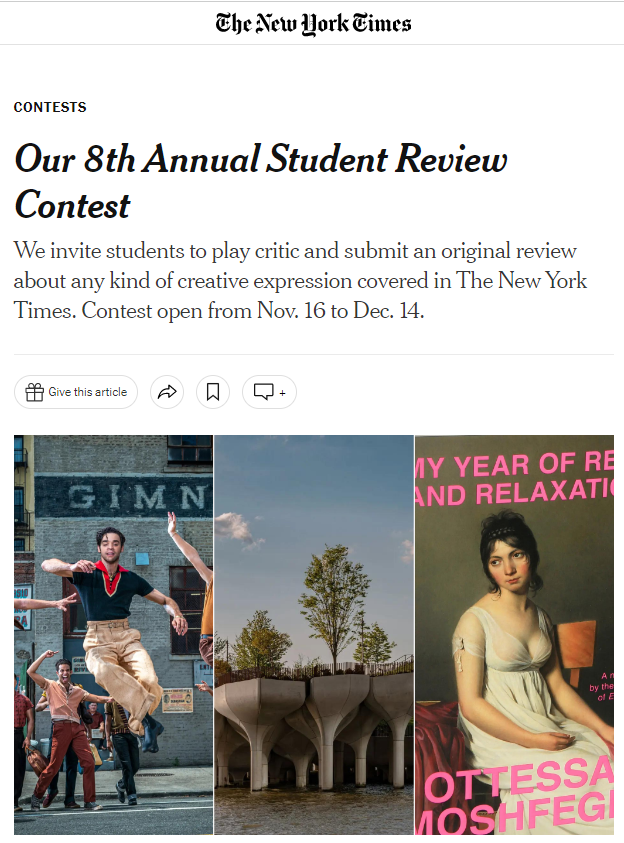

每年紐約時報都會開啟學生評論競賽。對於小作家來說,如果你喜歡對事物發表自己的想法和觀點,那你非常適合這個競賽。

在紐約時報評論競賽中,學生可以針對任何類型的創意作品進行評論,包括多類別主題。

Aralia特邀名師為大家帶來2020年紐約時報第八屆學生評論競賽獲獎作品詳細逐句分析,幫助同學們感悟獲獎作品的魅力,學習優秀寫作技巧,助力備賽第一步!

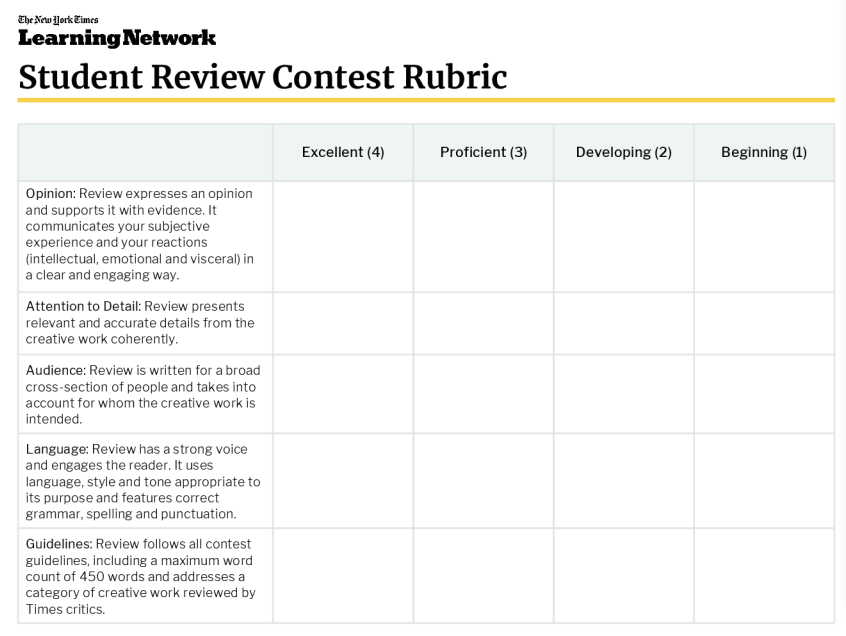

紐約時報學生評論競賽評分標準

紐約時報學生評論競賽關注到文章最終呈現的五點內容,並以此作為評分標準,分別是:

Opinion 觀點

評論表達了一種觀點,並以證據支持它。需要以清晰和吸引人的方式傳達參賽者的主觀經驗及對應反應(理解力、情感和內在)。

Attention to Detail 細節

評論中需連貫地展示了創意作品中相關且準確的細節。

Audience 受眾

評論是為廣泛分佈的人群創作的,需要考慮到創意作品的目標人群。

Language 語言

評論通過強有力的語言敘事來吸引讀者。使用適合其目的的語言風格和語氣,並具有正確的語法、拼寫和標點符號。

Guidelines 比賽準則

評論遵循紐約時報所有的比賽準則,包括最多字數為450字,並根據《紐約時報》評論員所評論的類別進行創作。

並通過四個分值:Excellent (4); Proficient (3); Developing (2) ; Beginning (1)來進行每一項的最終評判。

競賽評分標準是最好的文章指導和修改準則。通過對競賽評分標準的解析,有助於參賽者掌握評委的評分偏好,有助於對自己的回復進行適當地修改。

獲獎範文在滿足競賽評分標準的同時,又擁有獨特的創作思路與行文風格,讓我們一起來看看吧~

獲獎範文逐段賞析

以下文章來自2020年紐約時報評論競賽獲獎者Samantha Liu的參賽作品, Samantha來自Basking Ridge, N.J.

'Mulan'Remake Won't Make a Fan Out of You

“It’s about that time where Disney plunders a richer past for newly mediocre content, and, as of late, ‘Mulan’ is the unlucky victim. Director Niki Caro struggled to bring maturity to a cheeky original. Gone are shirtless Li-Shang scenes, wisecracking Mushu, infectiously upbeat songs; in their place, wuxia themes and sweeping landscapes. But underneath the diversity points for the all-Asian cast and the grandeur of a $200 million budget lies an empty story: forgettable at best, problematic at worst, satisfying nobody.”

名師解析:

文章開篇第一句話就奠定了作者的主旨基調,使用mediocre“普通的、尋常的”以及victim“受害者”等詞體現出了作者對於迪士尼新翻拍的電影《花木蘭》的個人態度。

緊接著,作者運用排比的修辭手法將電影中突出的幾個點陳列了出來,使得不熟悉此電影的讀者也有了初步的了解。

“Though the remake’s omissions from the original imply somberness, its jolts of absurdity found me balking. In the climactic battle scene, Mulan flings aside her protective armor — flamboyant, maybe, but a bit too ludicrous for an adult film. The juvenility doesn’t end there: There’s a witch who transforms into a million bats (and still manages to die from an arrow); the sets resemble dollhouses under oversaturated skies; and the gaudy costuming feels plucked from a princess movie counterpart.”

名師解析:

本段的開頭運用了讓步句,深入表達作者對於此次翻拍並不滿意。在論證層面,作者對於並將電影中具體的場景運用鮮明的形容詞進行了詳細的描述,比如花木蘭過於閃耀的戰斗場景,以及女巫擁有變身千萬隻蝙蝠卻死於箭下等。

在作者看来,这些场景使得电影较为幼稚化,在此处作者巧妙地运用比喻的修辞手法将玩具屋dollhouse与公主电影Princess movie相比。

“Caro’s slapdash historical references fare no better. As an addition to the original, a fortuneteller describes chi, the Asian medicinal force, except it’s degraded into a super juice of which Mulan drinks too much. Now, already jedi-like and chi-supercharged, she is literally incapable of doubting herself. I found myself searching for the stumbling, determined teenager of ‘I’ll Make a Man Out of You’ and received instead a Spiderman without Peter Parker. Without the 1998 protagonist’s endearing blunders, Mulan becomes as wooden as the staffs with which she trains.”

名師解析:

這一段的開頭就點出論點—-這部電影沒有完全參照歷史依據。作者將原版與新版電影的故事進行了對比:原版中的花木蘭更多的是一位“意志堅定”的青年,而現在的花木蘭在作者眼裡則更像一位武士。與此同時,作者還巧妙地運用了大眾熟知的Peter Parker“蜘蛛俠”這一電影深入地論證自己的觀點。

“But if the film seems childish for a heavy historical drama, it still fails to spark joy as a family movie. Thanks to ‘authentic cultural representation,’ which is to say, a Google Translate take on Chinese, all of the characters are austere and distant, poor caricatures of Oriental values. The soldiers, devoid of camaraderie, crack two jokes before being abandoned by Mulan altogether (in the original version, she taught the hypermasculine bunch to cross-dress to save the emperor), while the repeated ad nauseam slogan “loyal, brave and true” casts doubt on Disney’s mastery of the show-not-tell principle. Most of all, it was cringe-inducing to watch Mulan’s parents parrot honor over happiness, so stiffly and stereotypically Asian that they cannot embrace their own daughter. In her attempt to create traditional legitimacy, Caro succumbs to the impersonal, Western notions about Asia. The result is a movie without heart, laughter or warmth — a movie without Disney’s trademark.”

名師解析:

作者在本段開頭與上一段進行了銜接:上一段講述的歷史原因,作者這一段開頭闡述了本劇既沒有達到好的歷史劇的標準,又沒有達到合家歡電影的作用。

作者通過對士兵和花木蘭的家人的行為進行了舉例,指出導演所展示出的是“西方眼裡的亞洲”,同時指出了本電影並沒有體現出同類型電影的代表性特徵:感情豐富、輕鬆歡樂以及帶來溫暖。

“In 1998, the young Hua Mulan gazed introspectively into her mirror and sang, ‘Who is that girl I see / Staring straight back at me?’ If she were glimpsing herself 22 years into the future, doomed by future Disney’s obsession with garbled live-actions, she would be asking the same question.”

名師解析:

作者在結尾段運用了非常吸引人的設定(“原版中的花木蘭”盯著鏡子中的自己所唱的歌詞)來提出反問,使用諷刺的寫作手法再次來指出新版的失敗,展現了作者強烈的個人觀點。

原文鏈接:https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/24/learning/the-winners-of-our-sixth-annual-review-contest.html

範文總結

紐約時報官方給出的評分標準中包含:Opinion觀點、Attention to Detail細節、Audience受眾群體、Language 語言、以及Guidelines 比賽準則。

在本篇文章中,作者清晰鮮明並堅定地闡述了對於《木蘭》這個電影的觀點。

作者在整篇評論中運用了非常多的細節描述來強有力地支撐論點。同時,作者在文章中點出導演的名字,以及對於作品的熟悉度都能體現出作者詳細的研究以及思考的深度。

此外,在寫作敘述上,作者運用了多種倒裝句,排列以及引用,這些都是非常亮眼的寫作手法。